The Enigma of the Seychelles Mermaid: A Dive into Historical Mysteries and Maritime Folklore

The Seychelles Mermaid: A Melding of Myth and Marine Ecology

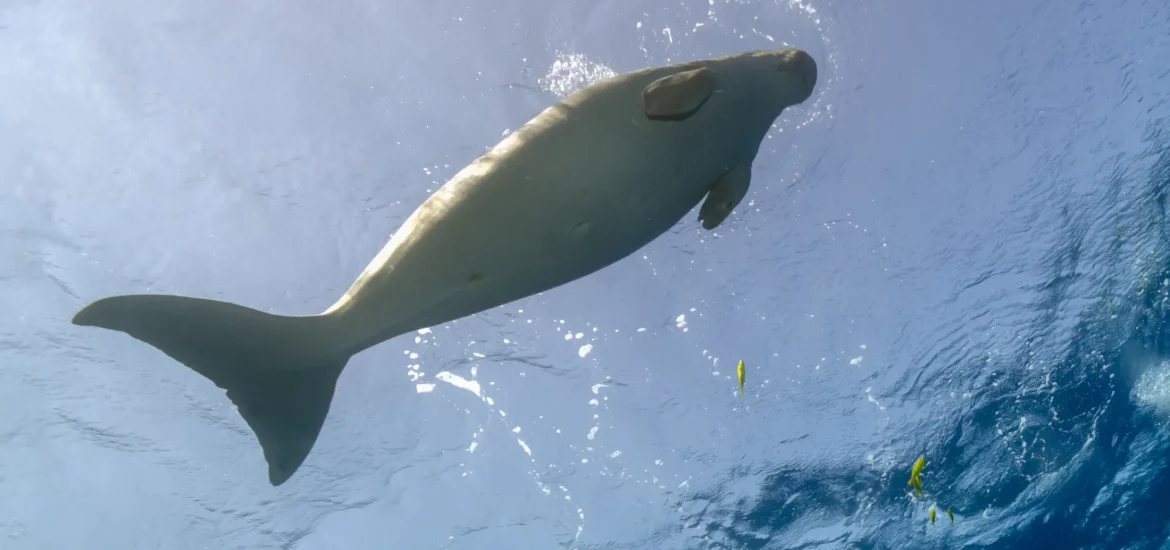

The Seychelles mermaid, often associated with the endangered Dugong, or the “Sea cow”, has stirred countless debates among historians, researchers, and marine biologists. The Dugong, a sea creature known also by several names such as “Lady of the Sea”, “Sea pig”, and “Sea camel”, is an endangered species that once frequented the lagoons of Aldabra in Seychelles.

These creatures, according to the folklore, were seen as aquatic mermaids, featuring prominently in the local mythology and seafaring narratives. The first stories of mermaids emerged in ancient Assyria, later finding a place in global cultures, thanks to fairy tales like Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Little Mermaid” published in 1836.

Many locals report personal encounters with these mystifying creatures. Anecdotes of a man nearly seduced by a mermaid on Frêgate Island, sightings of Dugongs mistaken for submarines during World War II, or tales of people vanishing only to return weeks later, claiming abduction by mermaids, continue to fuel the Seychelles mermaid mythos. These captivating stories transcend the realms of curiosity, opening doors to a deeper understanding of cultural beliefs and maritime ecology.

However, the increasing rarity of Dugongs and the absence of solid evidence of the Seychelles mermaid have raised questions. Were the stories mere figments of an active imagination or were they based on sightings of unknown unidentified seals, as some researchers suggest?

Such speculation takes us back to the early mariners’ accounts describing these creatures as semi-aquatic, suggesting that these might not have been Dugongs, but perhaps a different species that had adapted to survive predators or environmental changes. Nevertheless, these narratives only add to the allure and mystery of the Seychelles mermaid.

Cross-Cultural Resonance: The Mermaid in Global Folklore

Just as Seychelles mermaids have been woven into the local lore, stories of these aquatic humanoids have permeated global cultures, creating a widespread belief system that transcends borders. In Haiti, for example, these beings are revered as the “lords or gods of water”, shaping the narratives of those who live by and depend on the sea. Haitian parents often recount tales of beautiful mermaids abducting people, keeping them underwater for days or weeks, and releasing only a few. Similarly, Zimbabweans share such stories, instilling a widespread fear of these enchanting creatures. One particularly striking account from the 1960s tells of a woman, presumed missing, who emerged from a river completely dry. She shared her experiences in an underwater world, abducted by a mermaid who had been infatuated with her.

Historical Accounts and Sightings: Fact or Fiction?

Despite the numerous captivating accounts, there is currently no scientific evidence proving the existence of mermaids. This lack of concrete evidence, however, hasn’t stopped countless stories and alleged sightings from appearing throughout history. From Pliny the Elder describing mermaids washing up on Roman Gaul’s shores in AD 77 to Christopher Columbus’s diary entry detailing the sighting of three masculine-looking mermaids off the coast of Hispaniola in 1493, the lore of these half-human, half-fish creatures persists. There’s even an account from 1608 involving the British explorer Henry Hudson, whose crew reported seeing a mermaid in the Arctic Ocean, and a famous story told by the English pirate Blackbeard in the early 1700s, who convinced his crew to avoid certain waters in the West Indies by claiming they were inhabited by gold-stealing mermaids. Despite these stories, the naturalist explanation posits that most of these “mermaid” sightings were likely manatees, seals, or other marine mammals mistaken for the mythical creatures.

Mermaids have been a part of human folklore and myth for thousands of years, appearing in the stories of almost every culture worldwide. Their descriptions vary, from the beautiful sirens of Greek mythology to the monstrous sea witches found in other traditions, yet all these stories share the notion of a creature that is part-human and part-fish.

Throughout history, there have been alleged mermaid sightings reported across the globe. These include stories like that of a Mandarin Chinese fisherman from 1730, who claimed to have married a mermaid he captured off Lantau Island. Or that of the Japanese soldiers stationed on the Kei Islands during World War II, who reported being attacked by an orang ikan, an aquatic creature with a human face and limbs. In Thailand, where the coastal city of Songkhla houses an iconic landmark – the Golden Mermaid statues on Samila Beach. These statues are more than just a tourist attraction, they represent an integral part of Thai mythology. The mermaid, cast in bronze and coated in gold, rests on the sand, her tail curled towards the sea in a perpetual pose of playful elegance. Legend has it that a prince was set to marry this mermaid, but upon breaking his promise, she turned into stone. This story, steeped in romance and tragedy, embodies the Thai people’s belief in the magic of the sea and its mystical inhabitants. Like the Seychelles mermaid, the Golden Mermaid of Samila Beach is a symbol of the timeless human fascination with the sea and its mythical creatures, further adding to the global resonance of mermaid folklore.

The Mermaid in Modern Times: Sightings and Cultural Impact

In modern times, there have been sightings too. In 1967, passengers on a ferry in Victoria, Canada, reported seeing a mermaid with long blonde hair and the body of a porpoise sitting on rocks and eating raw salmon. In 1998, a group of scuba divers off the coast of Hawaii claimed to see a mermaid swimming with a pod of dolphins. In 2009, residents of Haifa Bay in Israel reported sightings of a mermaid that looked like a young girl with a fishtail.

Despite these alleged sightings and the widespread presence of mermaids in our myths and stories, there is no scientific evidence to support the existence of mermaids. Most of these tales and sightings can be explained by misidentifications of known marine animals, such as manatees, seals, or even large fish.

It’s also worth noting that the mermaid figure has permeated popular culture beyond folklore and alleged sightings. The Starbucks company uses the image of a Melusine, a two-tailed mermaid, as its logo, and P.T. Barnum famously exhibited a fabricated mermaid, called the Feejee Mermaid, in the 1840s. Today, mermaid costumes and monofin fish tails have gained popularity, with freediving training agencies offering mermaid courses to those who love the idea of these mythical beings.

While mermaids have long captivated the human imagination, there is no evidence to suggest that these legendary creatures exist outside of folklore and myth. That said, they continue to inspire stories, art, and even lifestyle choices to this day.

These stories, even if they seem unlikely, add depth to the discussion surrounding the existence of aquatic humanoids, contributing significantly to the rich tapestry of mermaid legends, including those of the Seychelles mermaid.

The allure of the Seychelles mermaid goes beyond its mythical existence, reflecting the rich folklore, diverse marine life, and the fascinating history of Seychelles. Even today, the tales of mermaids continue to stir the imagination, reminding us of our intricate connection with the sea and its creatures. Whether real or imagined, the Seychelles mermaid remains an enduring symbol of the island’s heritage, captivating the hearts of locals and visitors alike.